Torontonians awoke Wednesday to another installment in a

series of ambitious but controversial transit plans. Unlike its

predecessors, the City of Toronto’s Transit City and the Government of

Ontario’s MoveOntario 2020, the new OneCity plan proposes to rely on the

property tax base rather than the strained provincial budget as its

primary source of funding. This alluring but flawed program is a further

example of the politics-driven planning that has dominated Toronto

transit discussion in recent years.

OneCity was unveiled by two councillors, Karen Stintz and Glenn De Baeremaeker, respectively aligned with the right and left factions on City Council but both hostile to Mayor Rob Ford. Stintz, as chair of the TTC, launched a coup that humiliated the mayor by removing his allies from the commission when they attempted to replace the Transit City light rail plan with underground rapid transit lines. This announcement is intended to further marginalize Ford by proposing a new scheme involving tax hikes to fund transit expansion without consulting the vehemently anti-tax mayor’s office. Unsurprisingly, the reaction from the provincial government and Minister of Transportation Bob Chiarelli was dismissive, given the desire to draw a line under the tumultuous debates that have thrown transit planning into disarray in recent years. Studies are complete and contracts are being signed for the current Transit City projects, and the province will not risk further delay.

Nevertheless, the OneCity plan has reshaped the ongoing debate about Toronto’s transit future. Its willingness to explore subway expansion is a dramatic shift from the exclusively light rail Transit City plan. Moreover, the endorsement of a property tax increase to expand the TTC’s capital budget by councillors that span the political spectrum suggests that the prospect of new funding sources is less fantastic than it had previously appeared to be.

Like MoveOntario 2020, OneCity follows the 'kitchen sink' approach to planning, incorporating virtually every municipal transit scheme from the last two decades and adding a few more of its own. It includes all of Transit City, a plan that boasts of bringing streetcars or light rail to every councillor’s ward, as well as the newly fashionable Downtown Relief Line and Sheppard West subway extensions. Historic streetcar routes would be extended while bus lanes would be built in several suburban corridors. Transit access to Pearson Airport would vault from the present Rocket bus to a regional rail 'express line' along the Weston rail corridor and two light rail connections along Finch and Eglinton.

The plan employs an esoteric modification to the property tax in order to capture the increasing value of Toronto real estate. Rather than reducing the mill rate to keep revenues stable as assessments increase, the rate would drop by a smaller amount and 40 percent of the assessment increase would be dedicated to transit expansion. It is intended to provide a consistent revenue stream of $272 million per year. While it will undoubtedly face opposition from anti-tax forces including the current mayor, a gradual increase in the property tax is likely to fly under the radar in comparison to highly-visible road tolls, while escaping the need for further appropriations from a provincial government that is risking a bond rating downgrade. On the other hand, dependence on a consistent increase in property assessments could become perilous in the event of a real estate downturn. The most problematic aspect of the plan is its lack of regional scope, being limited to the boundaries of the City of Toronto. It bypasses the admirable steps toward GTA-wide planning that have been taken by Metrolinx. Funding sources that are truly regional in scope will be needed to build a comprehensive regional transit system.

The most exciting aspect of the OneCity plan is its tentative endorsement of genuine regional rail as part of the GTA’s mix of transit modes. This is an unfamiliar concept to North Americans, but Europeans would be familiar with systems like the French RER, German S-Bahn, and the new Crossrail in London. These systems primarily employ existing rail corridors but operate a type of service that is much closer to a Toronto subway than to GO Transit commuter rail. Trains are electrified and operate at frequencies of up to every ten minutes. They are fully fare-integrated with local transit systems, so a rider can conveniently transfer from bus to regional rail to subway without paying an additional fare. This allows the regional rail line to operate both as an inter-regional connection and as a local rapid transit backbone in both the city and the suburbs. (Regional rail and its applicability to the GTA will be explored in future posts.)

OneCity reinforces the presence of the Downtown Relief Line in all serious discussion of the city’s transit future. Not only does the line improve access to areas of the central city that are undergoing rapid redevelopment and which already see high transit use despite often slow and unreliable service, but it also relieves overcrowding on the existing subway system. Particularly with its extension along Don Mills to Eglinton, the relief line will also capture riders from the Yonge line, reducing severe Yonge overcrowding and permitting its extension into York Region. The OneCity maps show the relief line ending abruptly at Queen station, though it would almost certainly continue at least to Spadina in the west. A Downtown Relief Line could function very effectively in concert with regional rail lines, serving local trips in the central city while regional rail would capture much of the traffic from Scarborough and the 905 suburbs.

Toronto is blessed with a transit culture that is extraordinarily strong by North American standards, but this has the unfortunate side effect of massive overcrowding on many routes. Toronto’s subways, streetcars, and buses are extremely well used, meaning that, unlike in many American cities, if you build it they will come: almost all new transit projects in Toronto will be well-used by international standards. Many cities would be immensely envious of the much-maligned Sheppard subway’s ridership; the Don Mills station is busier than the New York City subway's Atlantic-Pacific interchange in Brooklyn which is served by nine different subway lines. Toronto is long overdue for a major expansion of its rapid transit network, and the OneCity projects would go a long way toward improving service for existing TTC riders and accommodating continuing growth.

Nevertheless, some of the included projects are of dubious merit. Despite the addition of two rapid transit routes to relieve the Yonge subway and prevent the need to rebuild the Bloor-Yonge interchange, OneCity still includes the billion-dollar station reconstruction. The Toronto Zoo would bizarrely receive its own $170 million light rail line, though it was unable to support even its own seasonal express bus route. Presumably it would be shut down for nearly half the year, unless the TTC is able to find some way to collect fares from the squirrels and racoons of Rouge Park.

By incorporating so many recent plans, OneCity suffers from the line-on-a-map approach to planning that has become unfortunately prominent in Toronto. Residents are deemed to be 'served' by transit infrastructure merely by virtue of it passing within a certain distance of their homes, regardless of whether it takes them where they actually want to go in a reasonable time. The Sheppard and Scarborough-Morningside lines bypass Scarborough Centre, even though it is by far the largest concentration of office, residential, and retail development in the area as well as the borough’s largest bus hub. The Ellesmere BRT is intended to serve trips from Durham Region, but a hypothetical trip from Pickering to North York Centre would require no less than three transfers. Highway 401 was built on an entirely new corridor determined through origin-destination studies so that it served real trips as well as possible. This explains its extraordinarily high traffic. Metrolinx has undertaken similar studies in recent years, and they should be used to develop a genuinely comprehensive plan for the region without merely rehashing municipal plans that have been collecting dust for decades.

Transit expansion in the Toronto area has been crippled by the extraordinary inflation of construction costs over the past decade. The cost estimates included in the plan betray a continuation of this damaging process. The Scarborough-Morningside LRT has ballooned to $1.845 billion from $1.078 billion in the Transit City plan only three years ago, an eye-popping price for a surface light rail line to replace a bus route that is far from the TTC’s busiest. The vastly more complex Canada Line in Vancouver—more than half in tunnel and including two large water crossings—was scarcely more expensive despite being half again as long as the planned Scarborough route’s 12.5 km. Even more bizarre is the cost difference between the eastern and western regional rail corridors. Despite comparable length, the former is priced at $6.9 billion while the latter is planned to cost only $1.5 billion. Even allowing for the infrastructure in the western corridor already built for the Airport Rail Link, the eastern corridor cost estimate is astounding for a surface rail line in an existing rail corridor. The entire 350km Brussels RER project including substantial tunnelling is projected to cost €2.173 billion (C$2.8 billion). Though the existing Belgian infrastructure certainly requires less upgrading than Toronto's rail corridors for regional rail service, such a striking difference suggests a model for emulation. (Toronto’s rapid transit construction costs will be explored in future posts.)

OneCity is not likely to ever be implemented in its entirety, but it will have a substantial influence on future transit plans in the Greater Toronto Area. Its inclusion of substantial subway expansion, including a Downtown Relief Line, as well as rapid transit regional rail service on existing rail corridors, is a significant step toward meeting the pressing transit needs of both the central city and the broader region. OneCity also recognizes that the provincial government will be unable to provide the immense cash infusions that GTA transit has enjoyed in recent years, making new funding sources essential to avoid a repeat of Toronto transit’s two lost decades. The plan is, however, beset by significant weaknesses. It was clearly developed without serious study as to where expansion is genuinely needed in order to reduce congestion on existing routes, improve travel times and reliability, and encourage people to give up their cars. These three key objectives should be the basis for transit planning, and Toronto must reject the politically driven, “lines-on-a-map” approach in favour of rigorous analysis. Finally, any new funding source must be regional in scope in order to ensure that expansion does not stop at municipal boundaries and transit is not enmeshed in jurisdictional squabbles. Despite its flaws, the OneCity plan is a small but significant step toward a better transit future in the GTA.

OneCity was unveiled by two councillors, Karen Stintz and Glenn De Baeremaeker, respectively aligned with the right and left factions on City Council but both hostile to Mayor Rob Ford. Stintz, as chair of the TTC, launched a coup that humiliated the mayor by removing his allies from the commission when they attempted to replace the Transit City light rail plan with underground rapid transit lines. This announcement is intended to further marginalize Ford by proposing a new scheme involving tax hikes to fund transit expansion without consulting the vehemently anti-tax mayor’s office. Unsurprisingly, the reaction from the provincial government and Minister of Transportation Bob Chiarelli was dismissive, given the desire to draw a line under the tumultuous debates that have thrown transit planning into disarray in recent years. Studies are complete and contracts are being signed for the current Transit City projects, and the province will not risk further delay.

Nevertheless, the OneCity plan has reshaped the ongoing debate about Toronto’s transit future. Its willingness to explore subway expansion is a dramatic shift from the exclusively light rail Transit City plan. Moreover, the endorsement of a property tax increase to expand the TTC’s capital budget by councillors that span the political spectrum suggests that the prospect of new funding sources is less fantastic than it had previously appeared to be.

Like MoveOntario 2020, OneCity follows the 'kitchen sink' approach to planning, incorporating virtually every municipal transit scheme from the last two decades and adding a few more of its own. It includes all of Transit City, a plan that boasts of bringing streetcars or light rail to every councillor’s ward, as well as the newly fashionable Downtown Relief Line and Sheppard West subway extensions. Historic streetcar routes would be extended while bus lanes would be built in several suburban corridors. Transit access to Pearson Airport would vault from the present Rocket bus to a regional rail 'express line' along the Weston rail corridor and two light rail connections along Finch and Eglinton.

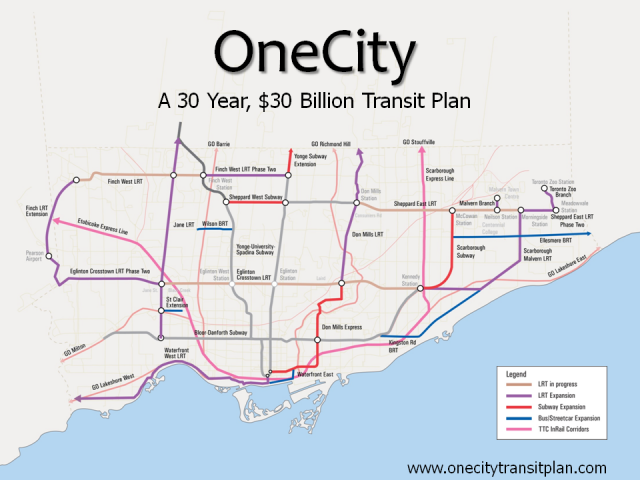

|

| Map of the OneCity plan (Source: www.onecitytransitplan.com) |

The plan employs an esoteric modification to the property tax in order to capture the increasing value of Toronto real estate. Rather than reducing the mill rate to keep revenues stable as assessments increase, the rate would drop by a smaller amount and 40 percent of the assessment increase would be dedicated to transit expansion. It is intended to provide a consistent revenue stream of $272 million per year. While it will undoubtedly face opposition from anti-tax forces including the current mayor, a gradual increase in the property tax is likely to fly under the radar in comparison to highly-visible road tolls, while escaping the need for further appropriations from a provincial government that is risking a bond rating downgrade. On the other hand, dependence on a consistent increase in property assessments could become perilous in the event of a real estate downturn. The most problematic aspect of the plan is its lack of regional scope, being limited to the boundaries of the City of Toronto. It bypasses the admirable steps toward GTA-wide planning that have been taken by Metrolinx. Funding sources that are truly regional in scope will be needed to build a comprehensive regional transit system.

The most exciting aspect of the OneCity plan is its tentative endorsement of genuine regional rail as part of the GTA’s mix of transit modes. This is an unfamiliar concept to North Americans, but Europeans would be familiar with systems like the French RER, German S-Bahn, and the new Crossrail in London. These systems primarily employ existing rail corridors but operate a type of service that is much closer to a Toronto subway than to GO Transit commuter rail. Trains are electrified and operate at frequencies of up to every ten minutes. They are fully fare-integrated with local transit systems, so a rider can conveniently transfer from bus to regional rail to subway without paying an additional fare. This allows the regional rail line to operate both as an inter-regional connection and as a local rapid transit backbone in both the city and the suburbs. (Regional rail and its applicability to the GTA will be explored in future posts.)

|

| The S-Bahn in Munich, an example of regional rail (Photo by Florian Derwarf) |

OneCity reinforces the presence of the Downtown Relief Line in all serious discussion of the city’s transit future. Not only does the line improve access to areas of the central city that are undergoing rapid redevelopment and which already see high transit use despite often slow and unreliable service, but it also relieves overcrowding on the existing subway system. Particularly with its extension along Don Mills to Eglinton, the relief line will also capture riders from the Yonge line, reducing severe Yonge overcrowding and permitting its extension into York Region. The OneCity maps show the relief line ending abruptly at Queen station, though it would almost certainly continue at least to Spadina in the west. A Downtown Relief Line could function very effectively in concert with regional rail lines, serving local trips in the central city while regional rail would capture much of the traffic from Scarborough and the 905 suburbs.

Toronto is blessed with a transit culture that is extraordinarily strong by North American standards, but this has the unfortunate side effect of massive overcrowding on many routes. Toronto’s subways, streetcars, and buses are extremely well used, meaning that, unlike in many American cities, if you build it they will come: almost all new transit projects in Toronto will be well-used by international standards. Many cities would be immensely envious of the much-maligned Sheppard subway’s ridership; the Don Mills station is busier than the New York City subway's Atlantic-Pacific interchange in Brooklyn which is served by nine different subway lines. Toronto is long overdue for a major expansion of its rapid transit network, and the OneCity projects would go a long way toward improving service for existing TTC riders and accommodating continuing growth.

Nevertheless, some of the included projects are of dubious merit. Despite the addition of two rapid transit routes to relieve the Yonge subway and prevent the need to rebuild the Bloor-Yonge interchange, OneCity still includes the billion-dollar station reconstruction. The Toronto Zoo would bizarrely receive its own $170 million light rail line, though it was unable to support even its own seasonal express bus route. Presumably it would be shut down for nearly half the year, unless the TTC is able to find some way to collect fares from the squirrels and racoons of Rouge Park.

By incorporating so many recent plans, OneCity suffers from the line-on-a-map approach to planning that has become unfortunately prominent in Toronto. Residents are deemed to be 'served' by transit infrastructure merely by virtue of it passing within a certain distance of their homes, regardless of whether it takes them where they actually want to go in a reasonable time. The Sheppard and Scarborough-Morningside lines bypass Scarborough Centre, even though it is by far the largest concentration of office, residential, and retail development in the area as well as the borough’s largest bus hub. The Ellesmere BRT is intended to serve trips from Durham Region, but a hypothetical trip from Pickering to North York Centre would require no less than three transfers. Highway 401 was built on an entirely new corridor determined through origin-destination studies so that it served real trips as well as possible. This explains its extraordinarily high traffic. Metrolinx has undertaken similar studies in recent years, and they should be used to develop a genuinely comprehensive plan for the region without merely rehashing municipal plans that have been collecting dust for decades.

Transit expansion in the Toronto area has been crippled by the extraordinary inflation of construction costs over the past decade. The cost estimates included in the plan betray a continuation of this damaging process. The Scarborough-Morningside LRT has ballooned to $1.845 billion from $1.078 billion in the Transit City plan only three years ago, an eye-popping price for a surface light rail line to replace a bus route that is far from the TTC’s busiest. The vastly more complex Canada Line in Vancouver—more than half in tunnel and including two large water crossings—was scarcely more expensive despite being half again as long as the planned Scarborough route’s 12.5 km. Even more bizarre is the cost difference between the eastern and western regional rail corridors. Despite comparable length, the former is priced at $6.9 billion while the latter is planned to cost only $1.5 billion. Even allowing for the infrastructure in the western corridor already built for the Airport Rail Link, the eastern corridor cost estimate is astounding for a surface rail line in an existing rail corridor. The entire 350km Brussels RER project including substantial tunnelling is projected to cost €2.173 billion (C$2.8 billion). Though the existing Belgian infrastructure certainly requires less upgrading than Toronto's rail corridors for regional rail service, such a striking difference suggests a model for emulation. (Toronto’s rapid transit construction costs will be explored in future posts.)

OneCity is not likely to ever be implemented in its entirety, but it will have a substantial influence on future transit plans in the Greater Toronto Area. Its inclusion of substantial subway expansion, including a Downtown Relief Line, as well as rapid transit regional rail service on existing rail corridors, is a significant step toward meeting the pressing transit needs of both the central city and the broader region. OneCity also recognizes that the provincial government will be unable to provide the immense cash infusions that GTA transit has enjoyed in recent years, making new funding sources essential to avoid a repeat of Toronto transit’s two lost decades. The plan is, however, beset by significant weaknesses. It was clearly developed without serious study as to where expansion is genuinely needed in order to reduce congestion on existing routes, improve travel times and reliability, and encourage people to give up their cars. These three key objectives should be the basis for transit planning, and Toronto must reject the politically driven, “lines-on-a-map” approach in favour of rigorous analysis. Finally, any new funding source must be regional in scope in order to ensure that expansion does not stop at municipal boundaries and transit is not enmeshed in jurisdictional squabbles. Despite its flaws, the OneCity plan is a small but significant step toward a better transit future in the GTA.

No comments:

Post a Comment