Toronto is facing a transportation crisis. We have more people using every form of transportation than any of the systems were designed to accommodate. Our best chance to expand rapid transit throughout the GTA for the smallest price is to add a new level of train service, referred to here as CityRail. This is the second in a series of in depth articles exploring aspects of CityRail.

This article is shared with Urban Toronto.

This article defines an ultimate scenario for various rail services in the Greater Toronto Area. It will explore rail corridor capacity to accommodate the maximum foreseeable level of CityRail service without excluding other corridor users. Using conservative assumptions based on international standards and a modern signalling system, it is clear that an extremely high level of service can be accommodated with a relatively limited expansion of the existing physical infrastructure. CityRail doesn't need billions of dollars of big infrastructure projects. In fact, it could be implemented with a handful of small targeted projects combined with the improvements Metrolinx is already undertaking.

This post assumes the establishment of three distinct levels of service, which mirrors most European systems. Within urban areas, there is a high frequency and frequent-stop rapid-transit-style service (such as the S-Bahn in Germany, Switzerland and Austria, and the RER in France), which would be CityRail in Toronto. It would run roughly to the edge of the developed urban area while towns and cities beyond would be served by a regional express service operating at lower frequency, like the RegionalBahn trains in Germany and TER in France. In Toronto, these trains would have on-board comfort similar to existing GO trains and would make only major station stops out to Niagara, Barrie, Kitchener, Cobourg, and perhaps Peterborough. An interesting option could be the provision of two service classes, with second class similar to GO and first class more like VIA, with reclining seats and food service. The final level of service is InterCity or high-speed service, which would offer a VIA Rail level of comfort and on-board service and be geared to passengers travelling distances greater than 100km. CityRail and the Regional Express services directly complement each other, with the former providing high-frequency and high-capacity for shorter trips while the latter provides the comfort and speed desired by passengers travelling longer distances. No single type of rail service could adequately serve all of Southern Ontario, but three levels of service will permit frequent stops and short headways for people travelling shorter distance while retaining comfort desired by longer-distance riders.

CityRail assumes the installation of a communication-based train control (CBTC) system in all corridors. CBTC uses modern wireless technology to keep track of exactly where trains are at all times. Rather than simply defining large sections of track that can only be occupied by one train at a time and notifying train drivers by signal lights, it can constantly maintain a safe space around each train that varies depending on the stopping distance required by each train at its current speed. It can greatly increase capacity on a line compared with current technology, particularly when different trains have different stopping requirements. It’s also a major safety improvement, since it makes absolutely sure that no two trains occupy the same track at the same time, and can even automatically stop an errant train without any intervention by its driver. Following a serious commuter rail crash in Los Angeles, the U.S. Congress has mandated that all American passenger rail corridors be equipped with such a system by December 2015. A state-of-the-art signalling system is the best way to add capacity to a rail network without spending vast sums on more tracks.

Adopting a signalling system that is compatible with the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) standard is by far the best option for CityRail. European countries have spent billions of dollars developing this most advanced signalling standard. Better yet, it’s not exclusive to a single signalling system supplier; instead, all major suppliers have developed systems that are compatible with the standard. This means that components and future upgrades can be obtained from whichever supplier is most economical. Standard North American signalling systems have received far less research and development investment and have far fewer competitive suppliers. They are also far less capable, explaining the comparatively poor performance of North American heavy rail lines. Freight trains would not share tracks with CityRail trains, so there is no need for freight operators to install ERTMS equipment in most of their locomotives. For the relative handful of trains that serve local traffic in the City of Toronto, a small subfleet of ERTMS-equipped locomotives could be maintained. VIA Rail is a relatively small operator, so the cost of re-fitting its equipment would be comparatively small. For some trains, it might be possible to use electric ERTMS-equipped locomotives while they run through the GTA and then replace them with diesels at the last electrified station. Any potential high-speed line would use ERTMS-compatible signalling anyway. There is the potential for bugs which would need to be worked out in order to make ERTMS work in North America, but a major new signalling installation like CityRail should use the most capable and widely available international standard.

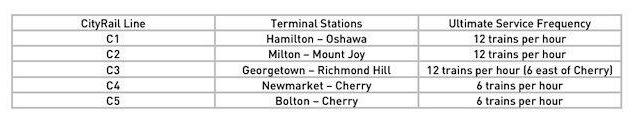

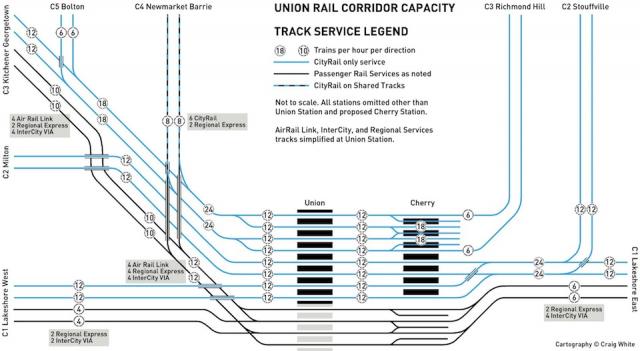

The diagram above describes an ultimate operating scenario in which CityRail is operating at high frequency on all corridors, while accommodating intercity, Regional Express, and Airport Rail Link services. This is meant to focus primarily on CityRail and is not meant to be an exhaustive or precise depiction of future rail service. For simplicity, it does not include the use of the North Toronto line nor services that run less than once an hour. I have assumed a relatively conservative maximum capacity of 24 trains per hour per direction on dedicated CityRail tracks (roughly every two and a half minutes) and 12 trains per hour (every five minutes) on other passenger tracks. For comparison, the busiest section of the RER accommodates over 30 trains per hour (less than two minutes apart), while the Munich S-Bahn tunnel handles 30. Crossrail in London will operate with 24 trains per hour per direction when it opens, expandable to 32. Some intercity corridors operate with even closer headways. While changes to regulations and operating practices will be necessary, the laws of physics are not different in Paris, so it is possible to run regional rail trains at high frequency in Toronto.

The main constraints on train frequency are the signalling system, train braking distance, train acceleration, dwell time at stations, and the need for fast trains to overtake slower trains. The installation of ERTMS would eliminate all signalling constraints. Train braking distance and acceleration would be greatly improved by operating lighter, more modern, electrified European standard trains, particularly for CityRail. It could be more problematic on non-CityRail tracks where VIA and other trains must share the corridor, which is why I have assumed a more generous 5 minute minimum headway. Dwell time at stations can be mitigated by rolling stock that is designed for rapid transit operation, with many doors and high floors. The Spanish Solution, involving a platform on both sides of the train so all doors can be used, is another option. At some stations, a two-track corridor could expand into four platform tracks so that a following train could pull into a parallel track as the one ahead is departing. Finally, the need to overtake is not so severe within the City of Toronto as frequent-stop CityRail trains will be in their own corridor separate from express trains. Regional Express, intercity and Airport Rail Link trains could all travel at the same speed through the city. Any conflict between non-stop intercity trains and stopping Regional Express trains could be resolved with passing tracks at stations. Changes to operating practices and regulations, combined with careful scheduling, will permit high frequency rapid-transit-style service on all CityRail corridors without requiring a massive investment in more track.

Lakeshore, Milton, Kitchener, and Stouffville (as they are currently named) are the CityRail corridors with the highest demand potential given the relatively dense areas and high-capacity connecting routes they serve. Richmond Hill, Bolton, and Barrie have somewhat lower potential given that they either closely parallel existing rapid transit routes or pass though relatively inaccessible or lightly developed areas for much of their length. I have therefore assumed a very substantial ultimate CityRail service of every 5 minutes on the former group and every 10 minutes on the latter. At the outset, trains would likely run at half as often. Lakeshore, Kitchener, and Barrie would also see up to 2 Regional Express trains per hour. The Kitchener corridor would have a separate pair of tracks for its Regional Express services, which would be shared with 4 Airport Rail Link trains per hour and two intercity or high-speed trains. The Lakeshore would also have a dedicated pair of tracks for Regional Express, intercity and high-speed services. As considerably more CityRail trains would be operating on the west side of the city than on the east, those trains would need a place to turn. Rather than carrying out that relatively time-consuming process at Union Station, the most valuable real estate in the city, I propose that it be done at a station on the site of the existing GO Don Yard at Cherry Street. There is ample space there for multiple platforms to turn trains, with the added benefit of serving the new West Don Lands and Port Lands developments. Toronto's rail network, with targeted improvements, can accommodate even a very high level of rail service.

The infrastructure expansion that would be required in the City of Toronto to provide even this extremely extensive ultimate level of service is relatively small. It would likely include:

- Building a dedicated pair of CityRail tracks in the CP Galt Sub (GO Milton) corridor.

- Expanding the Weston corridor to 4 tracks north of the Junction and 6 tracks south, which is already approved in the current Metrolinx EA.

- Expanding Lakeshore East to 4 tracks.

- Providing a continuous pair of tracks on the Stouffville, Richmond Hill, Barrie, and Bolton corridors.

- Flying (grade-separated) junction where the Bolton and Barrie lines enter the Kitchener/Milton corridor, and where Stouffville enters the Lakeshore corridor.

- A grade separation between the Milton corridor and the Kitchener intercity/ARL tracks.

- The re-alignment of tracks through the Union Station Rail Corridor to eliminate the need for different lines to cross and unnecessary switching.

- The addition of simple surface stations along all routes to serve dense development and major connecting bus, subway, and streetcar routes.

- A station complex at Cherry Street to turn and service trains.

- Electrification of all corridors.

Many of the improvements that would be required for the introduction of CityRail are already being built or planned by Metrolinx. However, their true potential is only unlocked with modern electrified, multiple unit rolling stock and advanced signalling systems. None of the projects listed above require lengthy underground construction or new corridors. In fact, almost all of it can easily be accommodated in the existing GO corridors. CityRail would add hundreds of kilometres of rapid transit to the GTA without needing to bore a single tunnel. The only needed physical plant is simple surface stations, selective grade separations, new tracks in existing corridors, and electrification. These are comparatively simple and inexpensive projects by the standards of rapid transit. The GTA is blessed with an extensive network of rail corridors, and if used to their full potential through the implementation of CityRail, they could greatly enhance transit service throughout the region.

I do not think that all items listed at the bottom of the document are really do-able given the space constraint. Quadru-tracking Lakeshore-East,double-tracking to Stouffville and a fly-over ramp at Scrb. GO station would need major expropriation of many resintial properties. This process alone would drag on for many years.

ReplyDeleteHowever change in operating mode of GO/METROLINX is desirable. There is only one GO train per-hour operating currently along Lakeshore on Saturday with huge latent demand unsatisfied. Why is that?

"CityRail assumes the installation of a communication-based train control (CBTC) system in all corridors."

ReplyDeleteYou don't NEED it! The table implies 5-minute headways, and lineside signalling can happily support 3 minute headways. The existing signalling system needs upgrading, not replacing.

Metrolinx already has long-term plans to quad-track the Kingston Sub and a flying junction at Scarborough Junction (where the Stouffville and Lakeshore East lines meet) should be quite easy to build. There's plenty of empty land around that interchange and flying junctions aren't that big: https://maps.google.ca/maps?q=48.960962,+2.324628&num=1&t=h&vpsrc=0&ie=UTF8&ll=48.960701,2.326119&spn=0.00472,0.011362&z=17&iwloc=A

ReplyDeleteThere's only one train an hour because GO operates with a mentality that it should run trains only when they're full. A rapid transit system doesn't work that way. Instead, it operates on a dependable headway so that riders can show up and go. That's why so many more people ride the subway than ride GO.

First of all, there are sections like the Kingston Sub between the Don and Scarborough Junction where 24 trains an hour would be operating on a pair of tracks, which all Metrolinx reports consider to be well outside the capability of our North American lineside signalling systems. Secondly, I don't see the advantage of not using the best and most modern available system to accommodate capacity increases indefinitely. ERTMS is also going to be improving all the time given the enormous investment the Europeans have made. Why not take advantage of that? What's so great about keeping and spending plenty to try and upgrade an inferior domestic system?

"First of all, there are sections like the Kingston Sub between the Don and Scarborough Junction where 24 trains an hour would be operating on a pair of track"

DeleteThere are three tracks there already. If you four-tracked it (a good thing to do), you would be talking ~12 trains/hour on each track.

"Secondly, I don't see the advantage of not using the best and most modern available system to accommodate capacity increases indefinitely." The advantage is that it would save money.

"There's only one train an hour because GO operates with a mentality that it should run trains only when they're full"

... yet GO is currently planning on a 30-minute off-peak service.

"There are three tracks there already. If you four-tracked it (a good thing to do), you would be talking ~12 trains/hour on each track."

DeleteI did say per PAIR of tracks for a reason: the other pair of tracks would be dedicated to intercity trains/high-speed rail/Regional Express trains. That's why there would be up to 24 trains per hour on two tracks.

"The advantage is that it would save money."

Not if we then need to replace the system 20 years down the line because it's inadequate. I'm not even convinced that it would be much cheaper to try to squeeze rapid transit frequencies out of an obsolete system. Moreover, regulators would definitely require PTC for any use of non-FRA compliant rolling stock, which would require overlay of PTC on the lineside signalling system. I'm definitely not convinced that all that would be less expensive than a turnkey ERTMS installation. I've never really understood why transit advocates are so fixated on saving money. There are plenty of other people who are more than happy to say too much is being spent on transit. We don't have car advocates denouncing a new highway for being unnecessarily wide or health care advocates denouncing a new hospital for being unnecessarily large.

"... yet GO is currently planning on a 30-minute off-peak service."

The key word is "planning." I'm sure it will happen at some point, but the fact that it has taken this long reflects the resistance to any model that deviates from "run trains only when busy."

This is a great series which is fulfilling the clear need for piecing all the parts together. It really shows what's possible when you have a clear endgame plan in mind.

ReplyDeleteMetrolinx needs to turn planning on its head and undertake a study which starts with a regional CityRail type network to begin with, then work backwards to assess the costs and benefits (when compared to other projects). This is opposed to the more traditional "what's the benefit of an single extra track here or there", which fails to recognize that the sum is greater than the individual parts. Steve Munro has complained that not enough network-level planning is undertaken. CityRail, a concept that is hardly unique and serves as the backbone of transit systems around the world, would be the best place to start.

A few years ago some citizens helped get the DRL back on the map, backed by the reasonable argument that spending billions of dollars on a new subway line was a better use of funds than spending billions of dollars on rebuilding a single station and upgrading existing infrastructure. Now is the time to see that spending millions or billions on increasing the efficiency and usefulness of the GO network is far more sensible than spending millions or billions to maintain current practices and only gain minimal improvements.

Deutche Bahn has a saying for dealing with problems... "policy before electronics before concrete". Jon's proposal contains the same concrete for new tracks as GO's plans. He's added some flyovers (tens or hundreds of millions of dollars), but removed a second Union station (billions of dollars). But, most fundamentally, he's tackled the questions of policy and electronics when no one else has.

Does anyone have a map of the current track layout? I can't get a picture of the flyovers west of Union. I'm trying to mentally work out the correct through-running couplets to get minimal interference using the current infrastructure.

ReplyDeleteObviously, Lakeshore East should flow through to Lakeshore West, and VIA Corridor rail should flow through on the same pair, with the services having a total of four tracks/platforms at Union Station. But it's less clear to me how to line up the northern branches. The flyovers mean it's not as simple as pairing them "outer to outer" until we get to the middle.